Welcome

What do you

want to do?

The TLC offers a broad range of support for instructors and TAs.

Check out the options on the right to get the support you need. If you don’t see what you’re looking for, contact us at tlc@ucsc.edu.

Equity Data Playbook

A collaboration between CITL, Online Education, HSI Initiatives, and Institutional Research and Policy Studies (IRAPS), the Equity Data Playbook allows campus educators and departmental leaders to observe patterns in student outcomes data and take evidence-based actions to transform equity issues.

Spotlight on Teaching

Magy Seif El-Nasr: Possibilities of Generative AI

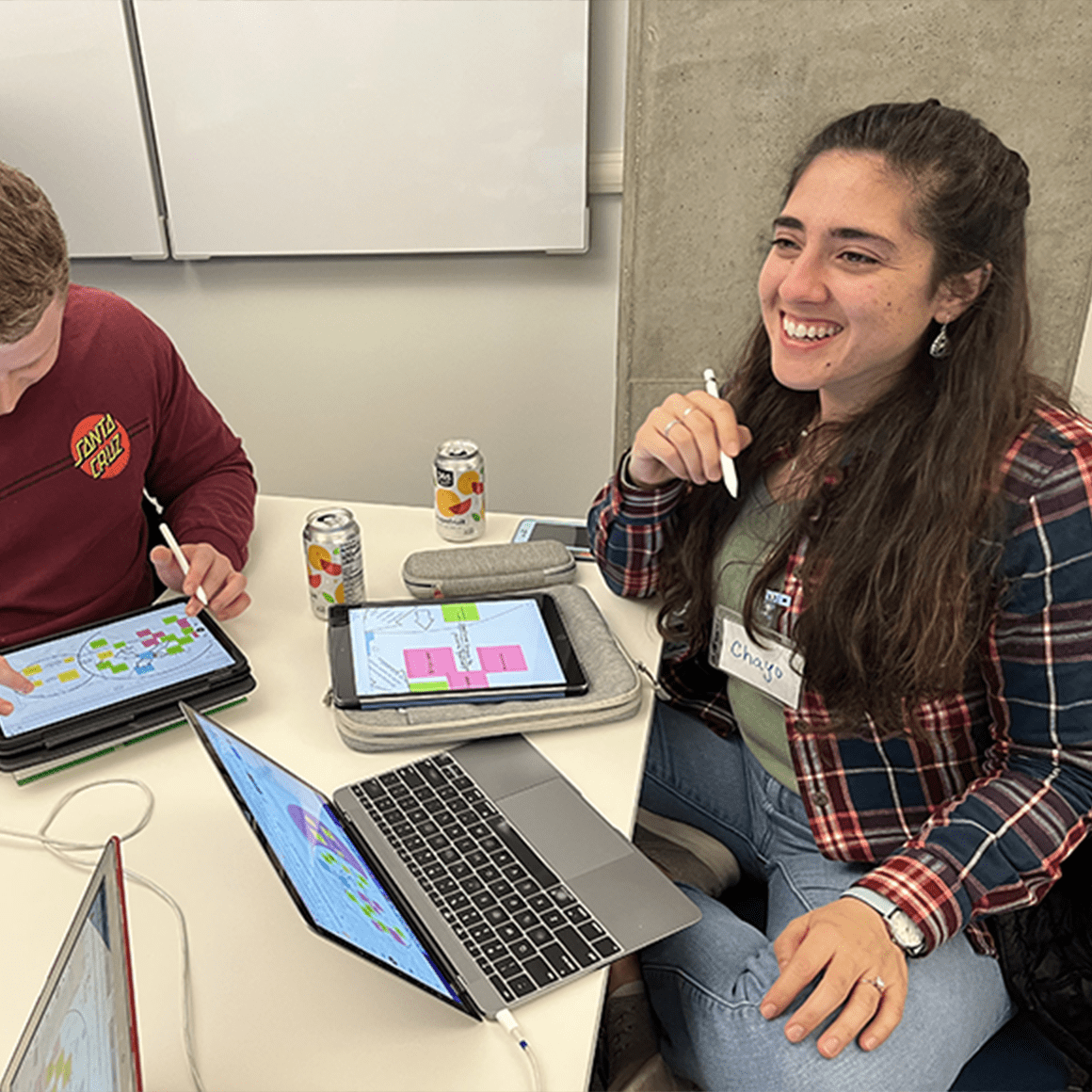

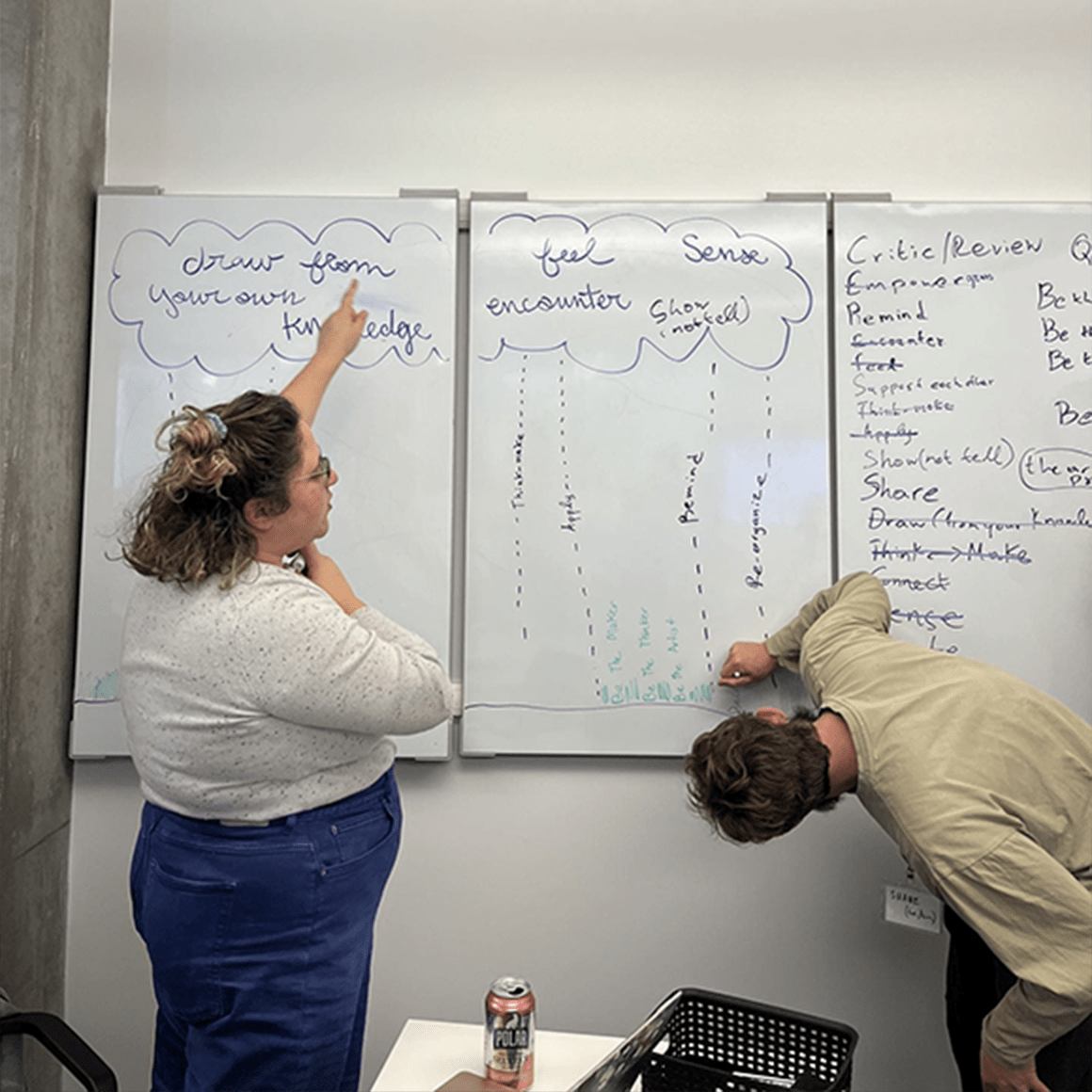

Many conversations about generative artificial intelligence in higher education are about academic integrity and threats to learning. Those issues are serious and challenging. But there is a generative side to generative AI, and some faculty, like Magy Seif El-Nasr, Professor and Department Chair of Computational Media, are helping both students and their fellow educators explore the new possibilities that generative AI offers.

The Teaching Newsletter

The Teaching Newsletter provides just in time resources and information you need for successful teaching and learning at UC Santa Cruz.